My trip to Australia has me thinking about the role of parents in the medical cannabis movement. In the 1990s, as the medical cannabis movement was moving towards its tipping point and the U.S. government was shutting down the only program of legal access to cannabis, Robert and I, through the Alliance for Cannabis Therapeutics (ACT), established an ad hoc group to honor the mothers of medical marijuana patients. These brave women often were at the forefront, demanding legal access to medical cannabis for their children (frequently an adult child). We called it MOMMS, Mothers of Medical Marijuana Smokers. Mae Nutt, affectionately known as Grandma Marijuana, was the honorary chairperson—more on Mae in a bit.

The title, MOMMS, is dated, reflecting a time when patients predominantly inhaled cannabis. But it is also only half the story. Perhaps we should have called it POMMS — Parents of Medical Marijuana Smokers. Not as catchy, perhaps, but more honest because the fathers are certainly an essential part of this long-running saga.

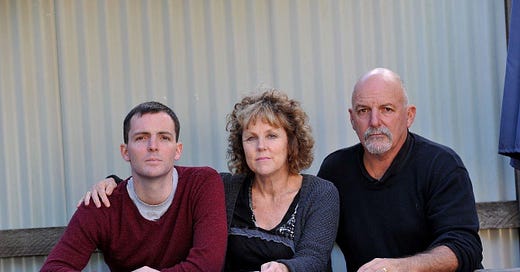

This thought was triggered as I attended the United in Compassion annual conference in Brisbane, an impressive event organized by the POMMS of Dan Haslam, a 25-year-old bowel cancer patient in Australia, who campaigned for medical cannabis before he died in 2014. His parents—Lou and Lucy Haslam—are an integral part of his story and the development of the medical cannabis movement in Australia.

Not long after his diagnosis, in 2010, Dan learned that cannabis might help with the terrible nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy but was hesitant to use it because his father was a retired vice cop. But Lou would hear none of it. “[G]o for it. Get some smoko. Anything to help my son.” His parents’ decision to support medical cannabis undoubtedly bought Dan some time and peace of mind. He was able to complete the first rounds of chemotherapy and went on to have “the best two years of his life,” according to Lou. (BBC, 2019) But the cancer roared back, and this time, it seemed Dan might not get so lucky. So, the Haslams made a bold decision to go public and campaign for change in Australian law so that future cancer patients would not have to rely on the black market. The Haslam family quickly became the face of medical cannabis in Australia.

Dan died in 2015. His courage inspired New South Wales Premier Mike Baird to authorize Australia’s first medicinal cannabis trial for terminally ill cancer patients. The Haslams set up an online petition supporting medical cannabis that drew 320,000 signatures and the government listened. On February 24, 2016, the Australian parliament legalized medical cannabis, one year to the day after Dan’s death.

No one would fault the Haslams if they had taken that victory and called it a day. Instead, they carried on, organizing United in Compassion, a charity organization dedicated to educating the public, politicians, and, especially, healthcare practitioners about medical cannabis.

Their story is reminiscent of Mae and Arnold Nutt, some of the first POMMUs to emerge in the late 1970s in the U.S. Their eldest son Keith was diagnosed with testicular cancer in 1977. When Mae heard about the use of marijuana by patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy, she startled her son by demanding that he “go out and buy some weed.” Keith complied, and the family was relieved when his suffering eased. But the cancer was too advanced, and Keith died in October 1979. (Marijuana Rx, O’Leary Randall)

Before his death, however, Keith and his parents became advocates for medical cannabis. Mae and Keith testified before the Michigan legislative assemblies in support of a medical marijuana bill based on legislation passed by the state of New Mexico just a year before. The bill was passed with overwhelming support and signed by the governor on the day Keith died.

Despite Keith’s death, Mae and Arnold remained committed to medical cannabis. They became active in the reform effort and established a local “Green Cross” operation. People would donate cannabis to Mae and Arnold, who would distribute it to cancer and glaucoma patients throughout Michigan. In 1988, they traveled to Washington, DC, and testified before the Chief Administrative law judge of the DEA. He later ruled cannabis should be rescheduled and cited part of Mae’s testimony in his decision.

Parents have continued to play a role in the medical cannabis politics of the 21st century. In particular, their efforts helped propel the approval of Epidiolex, the first cannabis-based medicine approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Its development was inspired by the parents demanding access to medical cannabis, in particular CBD, for their child’s intractable epilepsy. Epidiolex is pure CBD and prohibitively expensive unless the parents have a good insurance plan. Thankfully, CBD made from hemp is legal throughout the U.S. and parents can acquire quality CBD at a fraction of the price of Epidiolex. These products should be made available to more patients on an international basis. Until medical cannabis is globally available, the stories of parents championing the natural product for their children will continue to appear in every country.

Without question, great strides have been made to make cannabis legal for medical purposes, but there is still so much to do. In many places, cannabis is still illegal for medical use, and too often, in those places where it is legal, governments seem to go out of their way to make it difficult to obtain. So, patients and parents will continue to fight for a medicine that has always been a part of humanity’s medicine chest--except for the last one hundred years.

When it comes to cannabis, this is the true crime. ❖

Medicinal cannabis: The family that changed Australia's debate, BBC World News, July 2019

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-47796044

Marijuana Rx, The Early Years (1976-1996), by Alice O’Leary Randall

https://www.aliceolearyrandall.com/marijuanarxtheearlyyears